Today I met with Susan Hillier to chat about her experimentation with visual-motor feedback in a clinical setting.

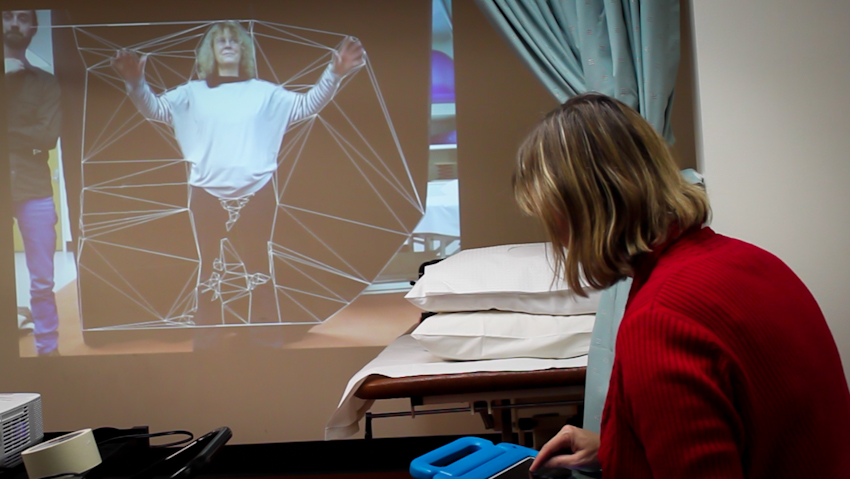

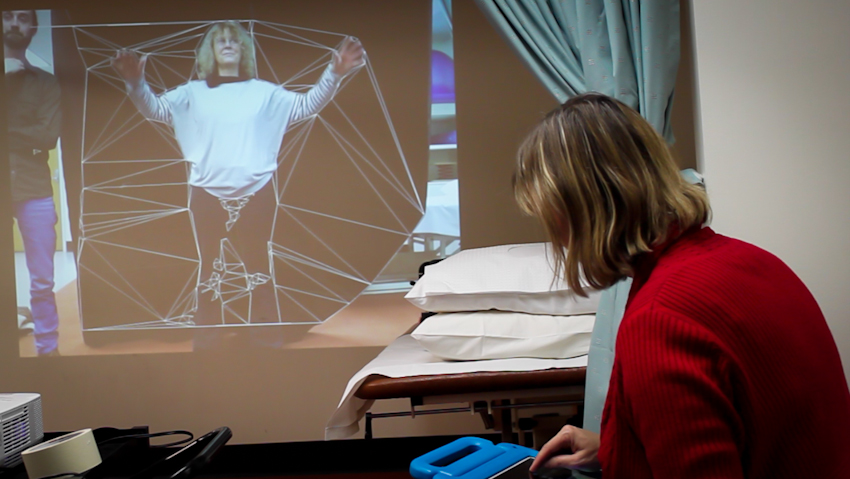

Last week I was an observer when Susan set up an experimentation session with Proximity Clinical software. The software has been provided through a collaboration with Australian Dance Theatre (ADT). ADT have made a bespoke version of the software for Susan and her team.

An extended play with this set up by Susan Hillier and Dan Harvie from BIM, lead into tests that were very similar to some visual – motor tests Melissa Hunt and I had done in the lead up to Somatic Drifts v1.0 in 2014. They were a lot of fun, initiated uncontrollable laughing in Melissa and lead to us both feeling dizzy and a little motion sick after a couple of hours of experimenting. The image is upside down, quartered, mirrored and flipped. We planned to revisit this in 2015 either in a new development of Somatic Drifts or for an entirely different artwork.

Susan is looking at the software’s potential use as a tool for therapy in stroke rehabilitation. It provides a kind of intervention into body image through visual-motor feedback. Susan and ADT’s collaboration was featured not long ago on the ABC 7.30 report.

She explains that at this stage she is evaluating the language used by patients experiencing Proximity Clinical in order to identify trends for further research. Through the experimentation phase she is also looking at patient responses to the different aesthetics of the video effects and describes this analysis as aesthetic metrics (I like this new term).

There appears to be an immediate (realtime) improvement in movement quality (timing/smoothness) and range while patients are in the experience.

It raises a number of questions: are improvements simply due to increased self attention or quality of attention?

Susan explains that the lead up and environment of an experience like this can make the brain more plastic. Information and environment prime the brain to make it amenable to change. This I know intuitively through artistic practice.

An environment (like an artistic environment) that removes distractions and confirms perceived safety allows the participant distinction of their body image.

One of Susan’s early observations is participants’ attraction to the webbing effect (pictured above) which surrounds the projected body. Participants show motivation to play with this image. We how the aesthetics of the image might extend the body representation to the space around the body. The participant gives attention to the negative space around the body.

It makes me think about the difference between this and attention within the body’s representative boundaries. An image comes to my mind of an interruption in the body representation (or signalling) within an affected limb (from stroke) that can be bridged when the representation (attention) extends past the interruptions beyond the body into the space around the body. Just like an electrical circuit can be bridged with conductive fluid. It seems to activate a leap.

Susan talks about how our body representation extends into the objects and materials that we are constantly in contact with or express ourselves through like pens, phones or cars. When we’re driving the car becomes an extension on the body. We feel bumps in the road through the car, and as if we are part of the car. Our sensory perception of the road surface changes.

All of these ideas have a strong resonance for me. Among many other things this conversation makes me think more of how attached people in Western culture are to objects and materials. How does this material relationship affect body representation. How does body representation differ in cultures that value and practice relationships to negative space, to country, to living organisms rather than inanimate materials?

Special thanks to Susan Hillier, Dan Harvie and the participant for letting me sit in.